BY ELISE CHIDLEY

Three miles on a dusty, bone-rattling road to school. When the potholes punched holes in the tires, we would pull over. My mother, with her long red fingernails, would expertly deal with jacks and spares on the stony shoulder while we kids looked out over the valley to the hillside shacks made of wattle, corrugated iron, and clay. On rainy days, the road became soft as warm chocolate, and the wheels would spin. We kids would get out and push. Sometimes the wheels spat mud over our red school dresses and white ankle socks. Sometimes the slush was so intractable that the car sashayed left and right as if the road were a serpent coiling and recoiling beneath the wheels. But no flat tire or mud mire ever prevented us from getting to school.

Three miles home. The turn off into the long road through the copse of wattle trees. The bump-bump over the cattle grid. The long run up the driveway with the dogs flying alongside in blurs of black and tan.

This was the landscape of my childhood. The trees did not match the books I read.

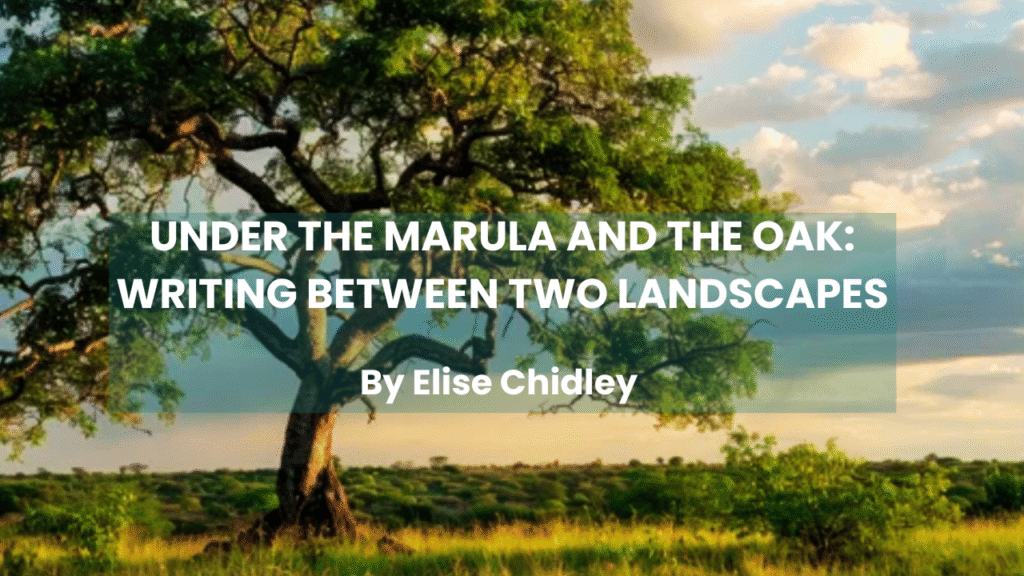

Take the marula, with its crooked branches and sun-split bark. It bears fruit that ferments where it falls, feeding birds and baboons and drunken legends. Or the flat-topped, thorny acacia, which defends itself so aggressively it looks braced for war. Or the fever trees with their smooth, greenish-yellow bark and their mysterious connection to malaria. Did they cause it? Cure it? The grown-ups never explained. Now, of course, I know they did neither. Their presence simply signified swampy conditions, where mosquitoes thrived.

The only European trees we knew were pines, invasive and greedy, swaddling the forest floor in drifts of brown needles that smothered most other growing things. Beneath these needles, if you had very sharp eyes, you could uncover edible mushrooms the size of dinner plates. You just had to look for the telltale mounding.

The pines weren’t the only invaders. Two of my favorite trees were imports from Australia. I loved the enormous and slightly surreal gum trees with their storybook-tall white trunks standing straighter than any indigenous tree. Gum tree bark peeled away in long, curling ribbons—white, gray, ochre, sometimes tinged with pink—streaking the pale trunks like watercolor paintings. The smell of the sap—sharp, medicinal—was the smell of potions, of magic.

I also loved the scraggly Australian wattles that all the grown-ups resented with a strange ferocity. When they were young and flexible, wattles were eminently climbable. As they matured, they produced long seed pods, pale green at first, darkening to brown, and these seeds were our coins and our earrings and our lucky beads. They flowered with bright yellow, puffball blossoms that looked like tiny suns and smelled of something more powerful than happiness.

Now, I understand that the black wattle is not so much a tree as a thirst with leaves. It draws up groundwater with frightening efficiency, leaving little to nothing for the native vegetation. It forms dense stands that block sunlight, alter soil chemistry, and crowd out biodiversity. And it cannot be eradicated. Cut it down, and it sprouts again from the stump. It seeds itself with wild abandon. It is the ultimate colonizer.

These were the trees of my childhood in Swaziland—now Eswatini—as important to me then as the roof over my head. But I was disappointed to find they were not the stuff of romantic poetry, of great works of literature. I never came across them on the pages of the books I devoured. Book trees were oaks and yews and elms. Maples and chestnuts and sycamores.

Now I live in Connecticut, and I am still learning to put the legendary names to the trees that grow around me, surprisingly tall and narrow.

In my small town, the oaks and maples are proud of their punctuality. They turn russet in October and drop their leaves as if they’ve all agreed to do so on the same day. They do not ferment on the ground or shed their trunks like snake skin. They are stately. Respectable. And most days, I find them lovely.

Still, there are mornings when I walk the dogs through our quiet neighborhood and feel a little melancholy. Not because the trees are not beautiful—New England has its own vocabulary of bark and branch—but because of the imposed order, the neatness. The lawns edged just so. The shrubs trimmed into obedience. Even the trees seem to know their place.

And I wonder: where do I belong in all this?

I’ve spent the last few years trying to restart a creative career I’d put on hold somewhere between raising kids and losing traction on the mud road of my writing life.

My children are grown now. The house is quieter, and the stories I want to write feel closer to the surface. I’m collaborating with two South African friends on a mystery novel set in southern Africa—invasive jacaranda trees, an elite boarding school, a disappearance—and it feels a bit like returning. Like finding my footing in the soil I thought I’d left behind.

But still, I write beneath oaks.

And maybe that’s what I’ve come to understand: we carry both landscapes inside us. The ungroomed beauty of native bush and the strange comfort of planted pine. The instinct to roam and the need for structure. I may have grown up with marulas, fever trees, and wattles, but now I spend my days under the trees of Thoreau, Frost, and Dillard.

The writing, I think, grows in the tension between those two forests.

Because writing, like a tree, needs both roots and reach. The stories I tell are twisted through continents—stories that come from the wild things I used to climb and the tidy things I now admire from the paved road.

And maybe that’s enough. Maybe that’s everything. To stand in one place while remembering another. To try hard to make something that grows crooked and true, wherever you are.